“The increased spread means that measles in the community could be an ever-present threat, not just confined to outbreaks,” says Peter Chin-Hong, MD, an infectious disease specialist and a professor of medicine at the University of California in San Francisco. “If the measles outbreak lasts for more than 12 months — which it is looking like it will in West Texas and New Mexico — it will be very probable that we will no longer consider measles eliminated in the U.S., because prolonged transmission of measles will continue, fueled by this very large outbreak.”

Dr. Chin-Hong notes that elimination (eradication) in the context of measles does not mean the virus is completely gone, but that transmission is at low enough levels to not be a major public health threat.

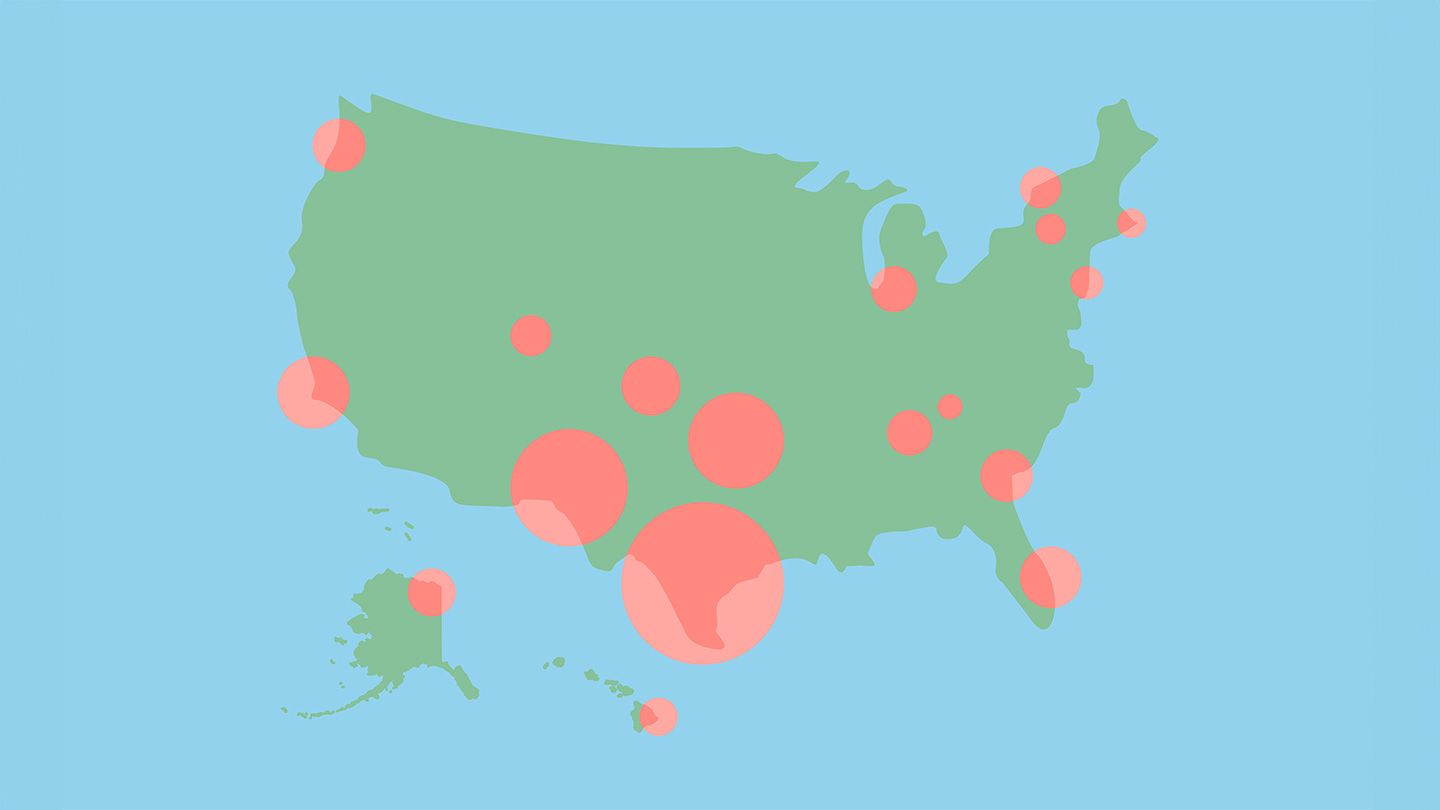

The Southwest Remains the Center, but the Problem Is Far-Reaching

Texas and nearby New Mexico and Oklahoma account for more than 80 percent of those infected.

Most measles infections nationwide have been among young people. Children under the age of 5 make up 30 percent of illnesses, while youngsters between ages 5 and 19 make up 38 percent.

Measles Can Be Deadly

Measles can cause serious complications, such as pneumonia and swelling of the brain (encephalitis) that may require hospitalization. About 13 percent of those infected this year have needed hospital care. Among this group, more than 75 percent were younger than 20.

A ‘Worrisome’ Decline in Vaccination

The authors of the CDC report stressed that measles outbreaks are becoming more frequent, especially in close-knit communities with low vaccination coverage.

“We’ve seen a worrisome pattern of decreasing routine childhood vaccinations,” said the senior author, Nathan Lo, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine specializing in infectious disease at Stanford Medicine in California, in a press release. “People look around and say, ‘We don’t see these diseases. Why should we vaccinate against them?’ There’s a general fatigue with vaccines. And there’s distrust and misinformation about vaccine effectiveness and safety.”

Immunization Offers the Best Protection

The measles vaccine is highly effective and safe, and because there are no antiviral medications to treat measles, immunization is the best protection, according to Chin-Hong.

Teens and adults are advised to check with their healthcare provider to make sure they are up-to-date on their MMR vaccination.

Most people who have received two doses of the MMR vaccine do not need a measles booster shot, but some specific individuals may benefit, such as those who have undergone certain treatments for cancer and have lost some immunity. Adults born between 1963 and 1967 should check with their healthcare provider to make sure they have immunity, as one formulation of the measles vaccine administered during that time period is considered less effective.

Read the full article here