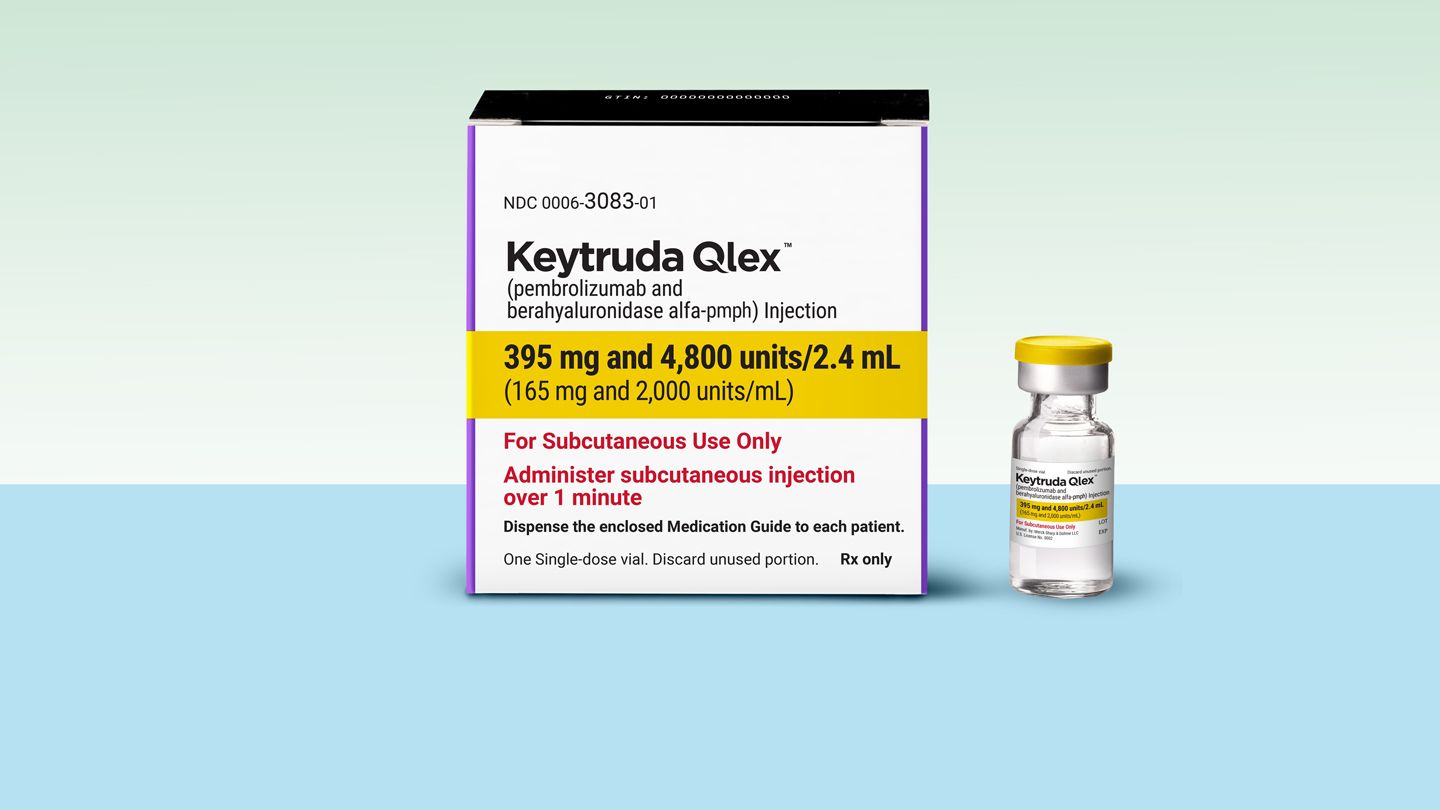

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a new injected version of the cancer drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) that may be easier for many patients to take than the older intravenous version of the medicine given through infusion.

The FDA approved the injected form, Keytruda Qlex, for a wide variety of solid tumors that have been treated with the intravenous form of the drug, including certain malignancies in the lungs, breasts, colon, head and neck, digestive tract and reproductive system, the FDA said in a statement.

The safety and effectiveness of both versions of Keytruda are similar, according to Merck.

With the injected version, “The main benefit is convenience and time,” says Pavlos Msaouel, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

What Is Keytruda and How Does It Work?

Keytruda was first approved in the United States in 2014. By 2023 it had became the world’s top-selling drug, prescribed to over one million people.

Keytruda is a type of treatment known as immunotherapy that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. Keytruda is in a family of immunotherapy medicines known as immune checkpoint inhibitors.

So-called checkpoint proteins on immune cells serve as gatekeepers that are supposed to keep foreign invaders from entering healthy cells. Certain cancers use these checkpoints to avoid detection. Immunotherapy drugs like Keytruda stop the checkpoints from hiding cancer cells, allowing the immune system to locate and attack tumors.

Keytruda Injections May Mean Less Time in Treatment Rooms

Injections of Keytruda only take about two minutes, compared with about a half-hour for IV infusions, according to Merck.

The shots allow patients to spend less total time in treatment rooms because healthcare providers can prepare and administer them more quickly, according to Merck. As a result, appointments for the shot take about an hour total, while appointments for the infusion take about two hours, per Merck.

“That’s important for busy infusion centers and for patients juggling work and family,” Dr. Masouel says.

Keytruda Shots Work as Well as Infusions

A late-stage clinical trial of Keytruda in combination with chemotherapy compared the effects of the injected versus the infusion forms in patients with stage 4 metastatic non-small cell lung cancer.

In the study, 45.4 percent of patients taking the injected form of the drug had tumors shrink or disappear after treatment, compared with 42.1 percent for the intravenous form.

So-called progression free survival, or the amount of time patients live without dying from any cause or cancer worsening, was about 8.1 months for patients on Keytruda injections, compared with 7.8 months with infusions, this late-stage trial found.

Slightly less than half of patients in this trial experienced side effects, regardless of which form of Keytruda they received. Among patients who took Keytruda in combination with chemotherapy, a certain percentage halted treatment due to side effects: 8.4 percent getting injections and 8.7 percent receiving infusions.

Treatment-related death rates were also similar, occurring in 3.6 percent of patients on injected Keytruda and 2.4 percent with the intravenous form.

Who Might and Might Not Prefer Injections Over Infusions

While convenience may motivate many cancer patients to opt for Keytruda injections, others may not find it a more efficient option, says Msaouel. Some patients — especially those who still require infusions for chemotherapy — may want to keep receiving Keytruda at infusion centers, he says.

These patients can get infusions for Keytruda at the same time as chemo infusions, so Keytruda shots wouldn’t reduce their total treatment time, Msaouel says.

Some patients may be hypersensitive or allergic to berahyaluronidase alfa, a component in the shots that makes it possible for the medicine to get absorbed under the skin, Msaouel says. While this issue is rare, people who are allergic to bees as wasps are more likely to fall into this category and may want to receive intravenous Keytruda, Msaouel advises.

“Patient preference matters, and both routes can be appropriate,” Masouel says. “Who should switch (or not) will be an individual decision based on medical history, logistics, and preferences after a balanced conversation with the care team.”

Read the full article here